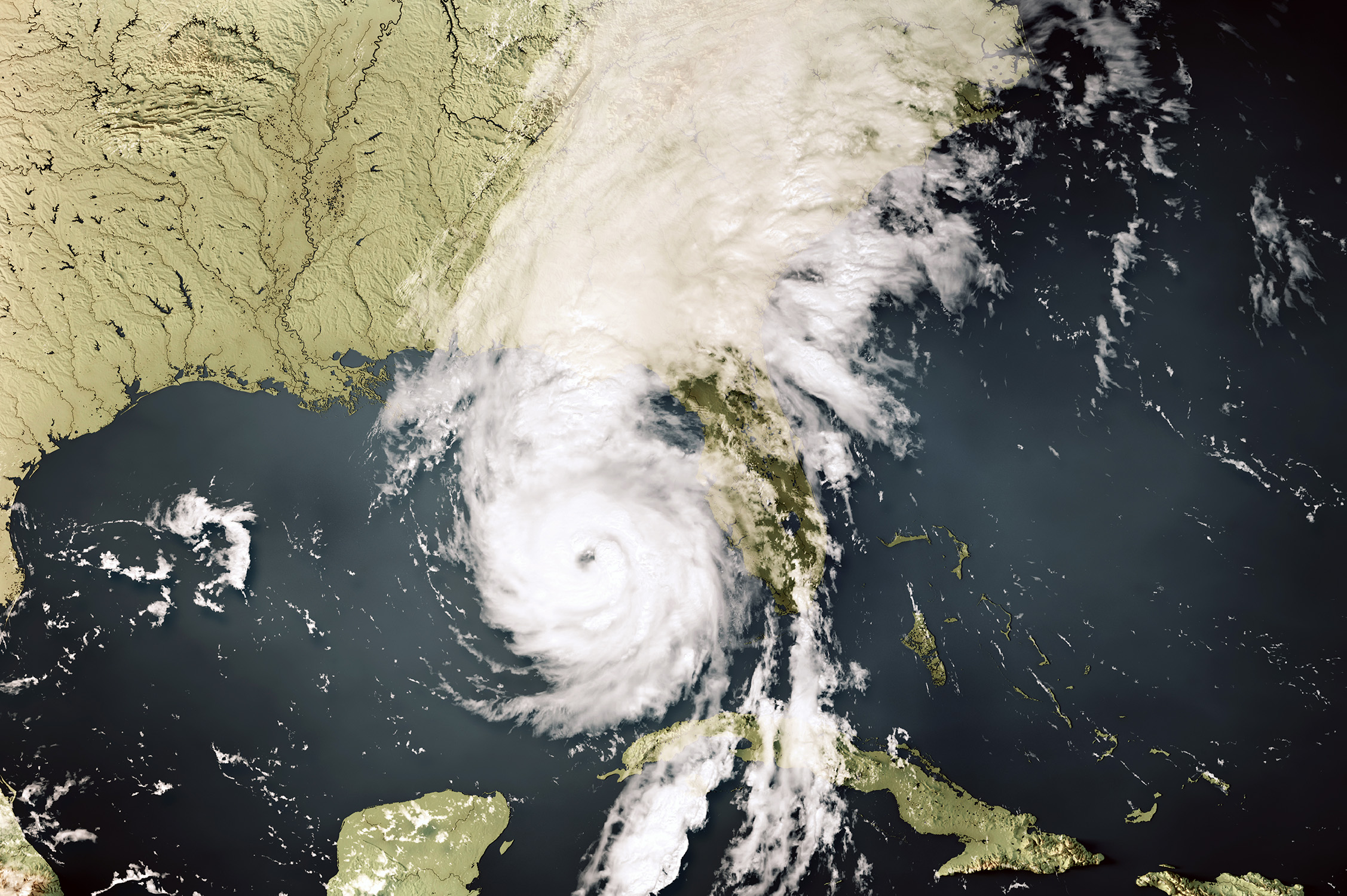

Hurricane Helene’s wind and flood damage in seemingly “safer” inland areas caught many people by surprise in late September, affecting six states: Florida, Georgia, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina and Virginia. Inland areas were not spared the hurricane’s wrath, as the storm dumped between 20-30 inches of rain and recorded wind gusts as much as 106 mph in some parts of North Carolina.

A few days later, Hurricane Milton developed and quickly exploded into a Category 5 hurricane, increasing rapidly over a two-day period to became one of the most intense hurricanes on record in the Atlantic, thanks to the Gulf of Mexico’s extremely warm waters. While the hurricane weakened significantly to a Category 3 storm by landfall on Florida’s west coast, the storm still brought extensive storm surge, significant rain, high winds and tornadoes. According to Reuters, this latest hurricane could cause up to $50 billion in insured losses for Florida property owners.

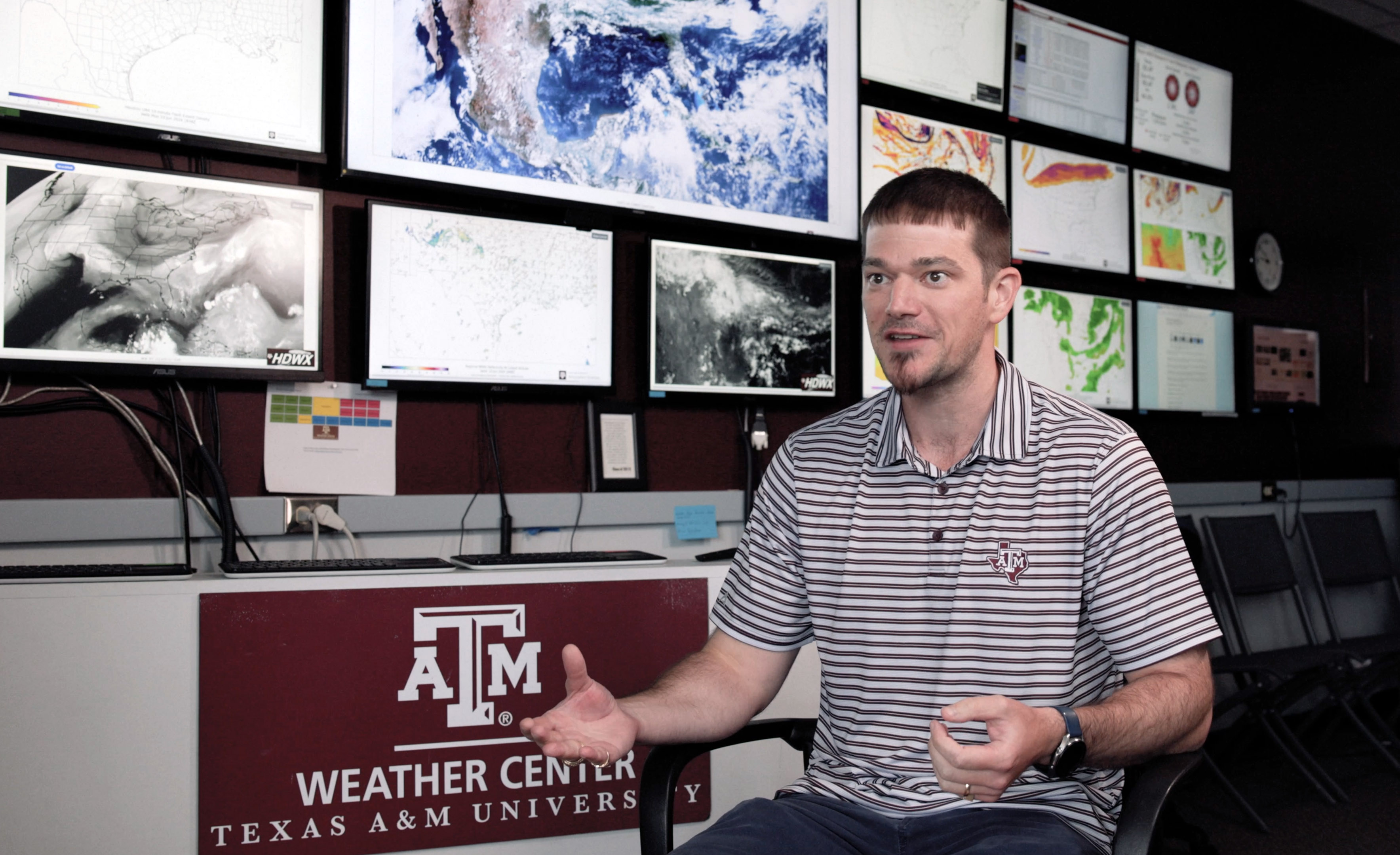

The potential for such types of destructive events is on the rise due to a rapidly changing environment, according to Texas A&M University atmospheric scientist Dr. Erik Nielsen.

“As the Earth’s climate system changes, we are going to shift what sort of weather events are possible,” Nielsen explained. “Events and impacts that we have not observed before might now occur. This will be a challenge for the meteorologists, emergency managers, city planners and others, as what our baseline of preparedness is and protective systems are, might no longer be adequate.”

Nielsen, an instructional assistant professor in the Department of Atmospheric Sciences and a 2013 Texas A&M meteorology graduate, is on the front lines of these changes through his work at Texas A&M. He’s preparing Aggie students to enter the meteorology profession with both excellent scientific and communication skills while exploring how meteorologists can better communicate weather information to the public so they can make more informed decisions about their well-being and property.

The Challenge Of Helene

Increasingly, Nielsen says meteorologists are facing a challenge in helping the public understand the multiple threats posed by powerful storms like Helene. “Hurricanes are multi-hazard events, with both wind and water threats occurring near the coast and inland” he added. “The predominant way we currently communicate the strength of a hurricane is the Saffir-Simpson scale, which is based upon maximum sustained wind speed alone. This scale does not represent any of the other water-related threats such as storm surge and inland flooding, which have unfortunately caused the most deaths in the last few decades. This creates a large communication challenge, as the main threat to people is not even accounted for by the ‘category’ of the storm, yet this is what is communicated most readily and easily by not just meteorologists.”

His research, which has included field experiments in the United States and Argentina, focuses on analyzing extreme rainfall, multiple weather hazards and the communication and interpretation of forecast information. “If we meteorologists create a perfect forecast but people do not understand or see it, that forecast has no value,” he explained. “In other words, to be the best meteorologists, we need to be excellent scientists who get the forecast right and excellent communicators.”

Additionally, individuals who live inland may not believe they need to take precautions because they haven’t had personal experience with these types of storms. “This creates challenges in communicating calls for protective action by both meteorologists and emergency managers because they must overcome the ‘category’ of the storm, individuals’ personal experiences, limited official communication pathways and something that seems impossible to imagine because it hasn’t happened before,” Nielsen explained.

He believes the National Weather Service, researchers, and other key stakeholders will be analyzing lessons from Helene for years. “After every event where there is a large loss of life, we need to evaluate what worked and what did not work,” Nielsen said. “We need to get out and talk to people — not just the public, but also local decision-makers. We need to see what information they were using to make decisions and how they were getting that information. We need to understand why decisions were made.”

However, personal factors play a part in everyone’s decision-making when facing these weather events. “We also need to keep in mind, as it is with any hurricane, that the ability to evacuate is a privilege that not everyone has for various reasons. This will help us better communicate forecast information and impacts to folks,” he said, adding a caution about the trend toward sensationalized weather forecasts. “We also need to limit ‘crying wolf,’ which is another challenge unto itself. There will not be a one-size-fits-all answer, but there is a multitude we can learn as part of the recovery processes.”

Growing Aggie Meteorologists

Nielsen, who originally is from San Antonio, explored all facets of his fascination with the weather while earning his undergraduate degree in meteorology from Texas A&M and his masters and doctoral degrees in atmospheric science from Colorado State University. “I am interested in all things weather, climate and how these things affect people,” he said. “There is a reason people, sometimes tritely, ‘talk about the weather.’ It affects every single one of us every day, whether we notice it or not.”

After completing a postdoctoral fellowship at Colorado State University, he returned to Texas A&M in 2020, joining the Texas A&M Atmospheric Sciences faculty and now working side-by-side with many of the professors who taught him. “It has been a really neat experience returning to Texas A&M as a faculty member,” said Nielsen, who also serves as the primary advisor for the Texas A&M Student Chapter of the American Meteorological Society and many high-impact-learning programs. “It helps me be a better teacher and mentor because I know the good and bad things students might be experiencing. I have also taken every class in the undergraduate meteorology curriculum as a student, so I know what questions my friends and I had in the class. This helps me develop materials that hopefully get ahead of confusion and make the learning environment more effective.”

His research, which has included field experiments in the United States and Argentina, focuses on analyzing extreme rainfall, multiple weather hazards and the communication and interpretation of forecast information. “If we meteorologists create a perfect forecast but people do not understand or see it, that forecast has no value,” he explained. “In other words, to be the best meteorologists, we need to be excellent scientists who get the forecast right and excellent communicators.”

Studying Concurrent Weather Events

Currently, Nielsen is working on two National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) projects related to the prediction and messaging around concurrent tornado and flash flood events that happen in the same location. “As it turns out, it is a fairly frequent occurrence that people can be at risk for both flash flooding and tornadoes or wind and water hazards more broadly,” he explained. “This is true for both hurricanes and more continental thunderstorms.”

This combination of flooding and tornadoes was prevalent with Hurricane Milton. Reuters noted that the hurricane dropped as much as 18 inches of rain in some places, while The Weather Channel reported a record 46 tornadoes in Florida, a state that typically averages 50 tornadoes during an entire year.

The challenge in these situations, Nielsen noted, is one of conflicting safety advice. “These hazards generally have opposite lifesaving calls to action: for flash flooding you go to higher ground, versus. seeking shelter in the lowest place possible in a tornado,” he explained. “Thus, it is imperative that the forecast of such events and the proper communication of what to do in these events is done in a manner that gets the proper messaging across to those in harm’s way.”

National Weather Service, broadcast meteorologists and emergency managers are in the roles they are because they care about the people they are informing. They are also part of the community that is being affected — and they are often personally affected in the same manner as the people they are informing. The information and advice they are presenting is not to cause alarm but hopefully to inform protective action.

Researchers are now analyzing how communication strategies, communication platforms and information can be used to create the most effective message in complex weather situations. “The mission of any meteorologist is to inform and protect,” he noted.

Yet, complex weather forecasts can make crafting a clear message quite challenging. “Accounting for all the human variables that affect interpretation of weather information is just as difficult, if not more so, than accounting for all the atmospheric variables,” Nielsen explained. “Our research shows that in situations with multiple, compounding weather hazards, a person’s vulnerability is magnified, so communicating lifesaving information must avoid complicating the situation and causing confusion.”

His research team also is focusing on improving forecasting of these complex weather situations. “We want to investigate ways to more accurately predict when there is a chance of multiple weather hazards to occur at longer timescales,” Nielsen said. “If we know there is a threat early, that changes how we communicate on several levels.”

Ultimately, Nielsen’s work is trying to support those who are committed to doing their best in trying to protect the public during these storms. “National Weather Service, broadcast meteorologists and emergency managers are in the roles they are because they care about the people they are informing,” he said. “They are also part of the community that is being affected — and they are often personally affected in the same manner as the people they are informing. The information and advice they are presenting is not to cause alarm but hopefully to inform protective action.”